Hank Edwards jokes that he’s been working in wildlife diseases, including chronic wasting disease, “since Jesus was in 4th grade.” The 26-year veteran of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department is the Laboratory Supervisor for the agency and works out of his lab in Laramie.

“The lab is about the size of this room,” he says, referencing the Coalter Loft in Lander where 30 people are attending Wyoming Wildlife Federation’s monthly Wildlife on Tap event. The space is filled with interested citizens, hunters, anglers, ranchers, and representatives from the local Game & Fish office who are all eager to learn more about wildlife diseases – especially chronic wasting disease.

Edwards gave a short overview on chronic wasting disease, his crew and laboratory in Laramie, and other diseases they are tasked with tracking, such as brucellosis, avian influenza, and Mycoplasma bovis – a deadly bacteria impacting pronghorn.

Since the Lander Region is home to the deer herd with the highest CWD prevalence in Wyoming (often referred to as the Project Herd), the majority of questions for the 2-hour session revolved around the prion disease. Edwards clarified that there are always more things to learn but he had confident answers to many important questions.

1. Can humans get Chronic Wasting Disease?

Largely, prion diseases stay along species-specific boundaries. Scrapie in sheep, Creutzfeldt-Jakob and kuru in humans, and others usually do not jump species, and that barrier seems to be stronger with CWD than the mad cow disease that made news in past decades.

“The fact is there is a substantial barrier but that barrier is not absolute, which is why the CDC recommends not eating animals infected with chronic wasting disease,” stated Edwards. He also pointed out that people’s risk tolerance spans the spectrum with some folks not eating positive animals, and some doing business as usual, positive or not.

2. Can animals be treated for CWD?

All animals infected with CWD meet an early demise, with deer death occurring 18-24 months after contracting it. Since it is a misshapen protein that causes holes in the brain, there are zero vaccinations or treatments to prevent or get rid of the disease once it has taken hold. The animal cannot form antibodies to a protein that is also part of a healthy body. Some research shows genetic variations of animals living longer with chronic wasting disease than others, but they still die from the disease.

“There were huge research trials with domestic sheep trying to [cure them] of scrapie (same disease, different species) that were unsuccessful,” Hank adds.

Providing better conditions for animals, like easy access to quality food, does not improve survival for those with CWD. They eventually show the classic signs of CWD, like confusion, drooling, and lethargy when they have 4-6 weeks of life left.

“Essentially when you see signs of CWD in an animal, that means they are circling the drain of life and are not long for this world,” Hank said. “They also only arrive at that place if their slower state doesn’t result in them getting taken out by predators, vehicles, or hunting before then.”

3. Why don’t we see a lot of carcasses in high CWD areas?

Since most deer with chronic wasting disease die within 2 years of contracting the disease, you can reasonably expect half of an infected population would perish in a given year. They don’t die all at once, though, the deaths are scattered across space and time.

Also, most CWD-positive deer are killed by what normally kills deer, just at higher rates, because of their reduced capacity. These might not be noticed by the average person as a deer that died as a result of chronic wasting disease.

“In Colorado, they have shown that archery hunters harvest a greater proportion of CWD-positive deer than rifle hunters because their brain functions are slower,” commented Edwards.

As most archers know, a deer with its wits about them can jump the string and dodge incoming arrows, or blow out at the slightest sound as a human sneaks into archery range. If they are mentally and/or physically compromised by CWD, they are taken out of the population quicker.

The archery hunter example is a good proxy for all other deaths that come from slowed senses caused by CWD, such as mountain lion kills and car collisions.

4. Are our deer herds doomed?

Since bucks start as twice as likely to be carriers of the disease, the deer herds are not endangered if it can be kept to a low prevalence and primarily in the buck population.

If there is a 20% prevalence in bucks, that is a decrease of 10% of bucks in the next year. With a productive herd, that is not a large enough portion to cause a major dip in the overall population.

Edwards suggests, “It’s when the female population gets [higher prevalence] that we should really worry,” because that means the disease is affecting their ability to produce the next generation.

“You do not get a do-over,” Hank emphasized related to the deer herd impact.

Once it has taken hold, it remains in the environment for at least 16 years. That would mean a long period of very low numbers, instead of a slightly lower density than the public may be aiming for today if we manage it properly.

The lab supervisor emphasized, “The important thing is the public needs to have patience with management actions, too. Because it’s a slow disease, any action we take to reduce the spread of CWD will take 5 to 10 years to see it come to fruition.”

5. How can people help?

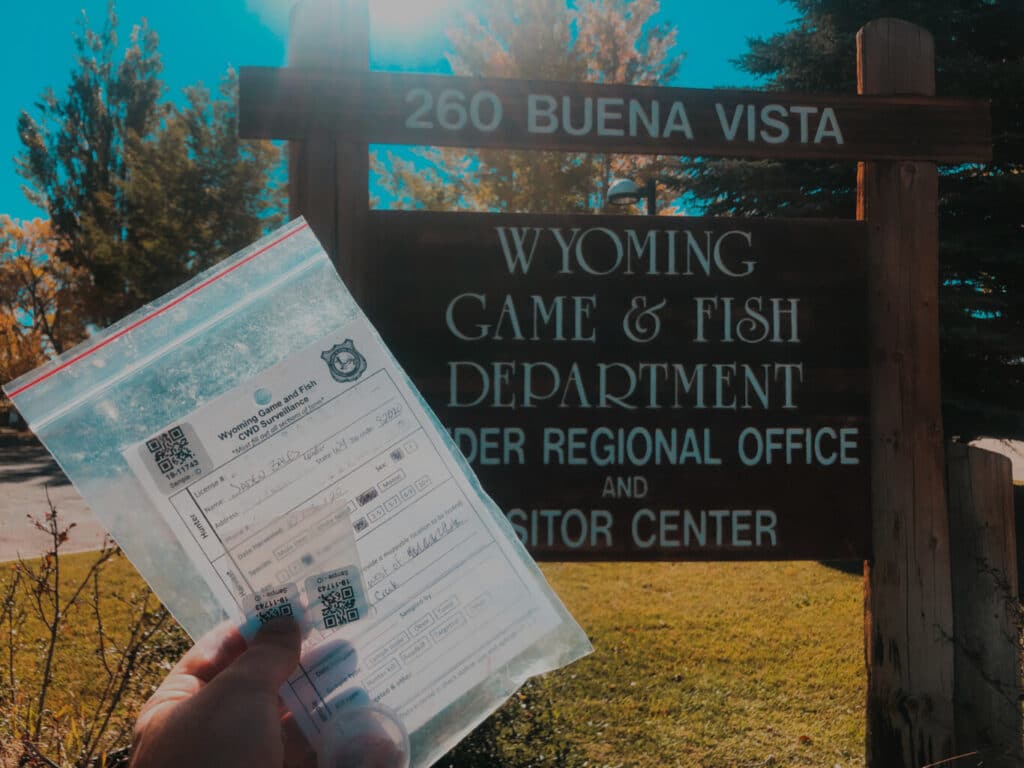

First and foremost, Hank asks that people get their susceptible animals tested. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department has been testing and monitoring this disease heavily since the early 2000s and the more data they gather about the slow spread of the disease year after year, the better they can make management suggestions.

Second, proper disposal of carcasses is important. Folks should take their deer, elk, and other carcasses to an approved landfill for disposal instead of kicking them out onto the landscape. Doing so prevents the disease from being spread to new parts of the landscape.

Also, supporting management actions as they are implemented will be critical to their potential for success.

One of the biggest barriers to Wyoming-specific research on CWD is the capacity of Hank Edwards’ lab. He and 4 full-time colleagues with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and two helpers on a federal grant run over 10,000 tests every year.

As I looked around the crowded Coalter Loft, it was impressive to think the skeleton crew at Wyoming’s Wildlife Health Lab is doing so much.

“We specifically do not have the time, personnel, nor lab capacity to chase down funding for additional research projects,” Hank added in relation to the passing of the national Chronic Wasting Disease Research and Management Act that put more federal dollars to studying the disease. On the bright side, people can expect more robust research coming from the APHIS-backed research facility in Colorado.

Supporting the expansion of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department employee cap and advocating for the Wyoming-specific agency is another long-term way people can help move the ball in the Cowboy State.