Wyoming’s ungulates – deer, pronghorn, elk, and moose- are on the move. Following patterns of weather, elevation, and food availability over eons has led to large groups of animals moving from low elevation areas in the winter to higher elevations in the summer. Spring migration offers animals the youngest, tenderest, and most nutritious plant growth at a time when extra energy is needed to produce the next generation. The reverse pattern allows the animals to minimize energy as they forage in deep snow conditions. These annual migrations are why Wyoming’s harsh winter landscapes can support the vast herds of ungulates we value today. The seasonal routes allow animals to move from summer to winter range and are critical to maintaining these herds.

Wild ungulates in this region have been following their migration paths for millennia. Today the potential impacts on these paths can impact the long-term health of these herds. Some issues are simple barriers, like fences. Others are more complex, like rural development, new roads, and energy development. These do not stop the animals physically but, alter the landscape to the extent few animals are willing to pass through. These semi-permeable barriers can also compromise stopover habitat; the rest stops on the migration routes animals use to refuel and rest along their journey. Bottlenecks, areas of migration routes where many animals pass through a very narrow band of habitat, also need protection. Disturbances in bottlenecks can put the entire migration at risk of being cut off.

The migration routes of ungulates across Wyoming are part of our natural heritage. They are part of what makes our state so wealthy in wild ungulates. Conserving these corridors while reducing and eliminating barriers to migration ensures that we will have healthy herds for the coming years and the next generation.

WHY DON’T ANIMALS MIGRATE SOMEWHERE ELSE?

Many animals, including ungulates, follow patterns of weather, elevation, and food availability moving from low elevation in winter to higher elevations in summer. This pattern, following young grasses and forbs, is called “surfing the green wave.”

In spring animals make use of the youngest and most nutritious plant growth. At this time extra energy is crucial to producing the next generation. The reverse pattern allows animals to minimize energy use while traveling in deep snow conditions. This movement pattern dictates a herd’s migration corridor. These are not point-to-point journeys but are vital habitat areas ensuring the survival of Wyoming herds. Animals spend almost 1/3 of their lives, when they are most vulnerable, on these corridors and pass this food knowledge to the next generation.

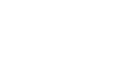

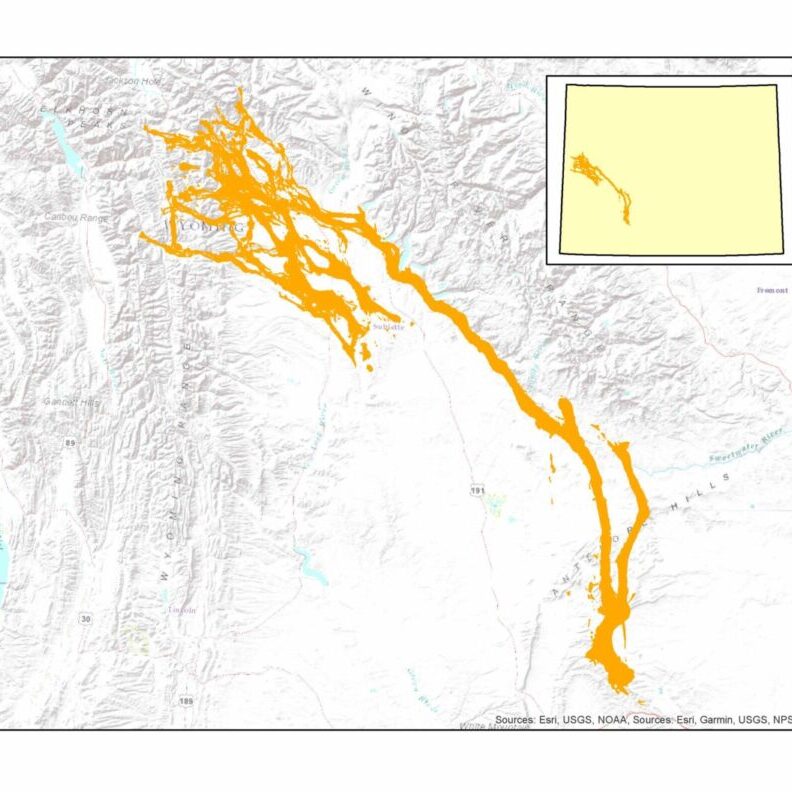

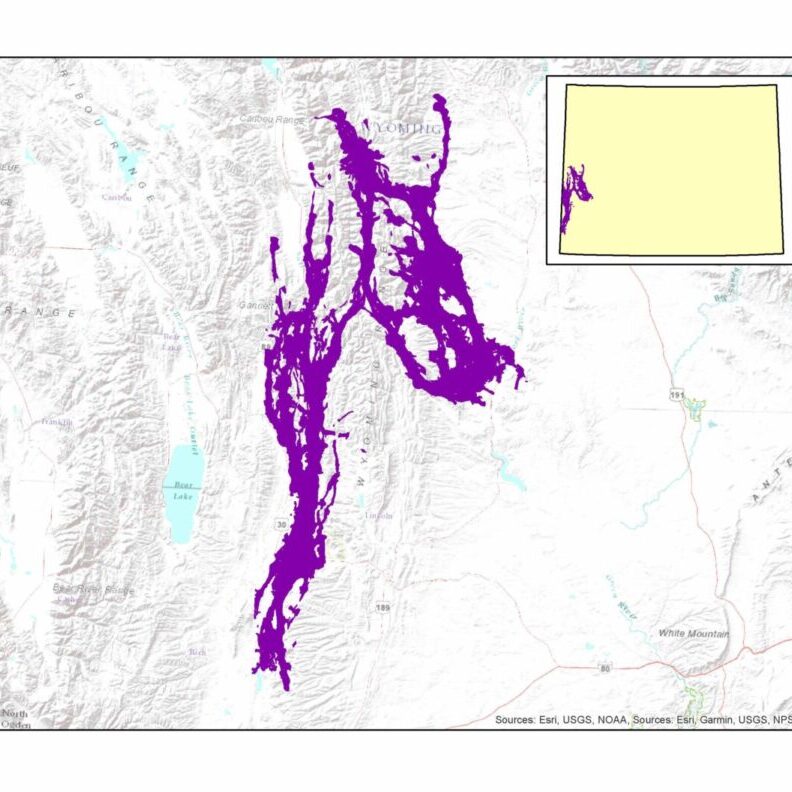

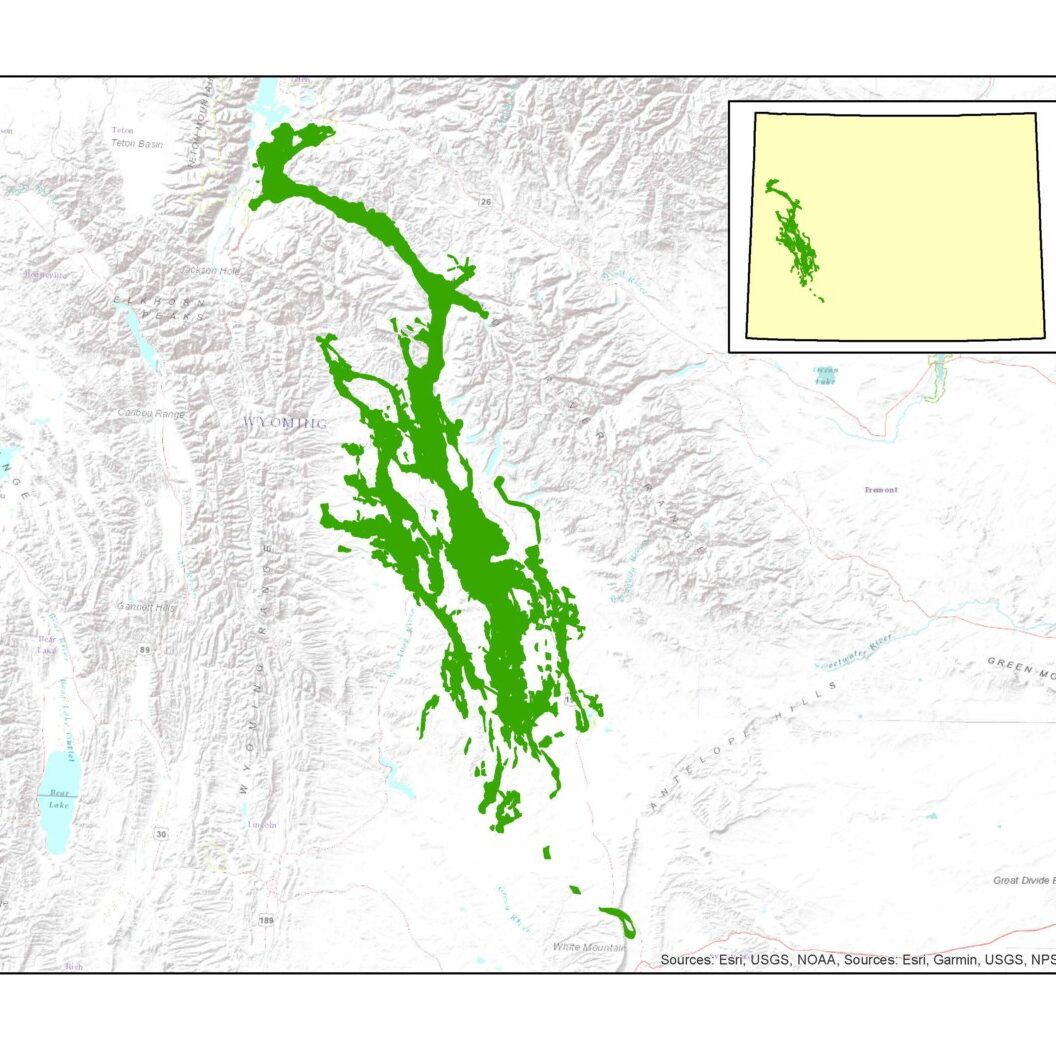

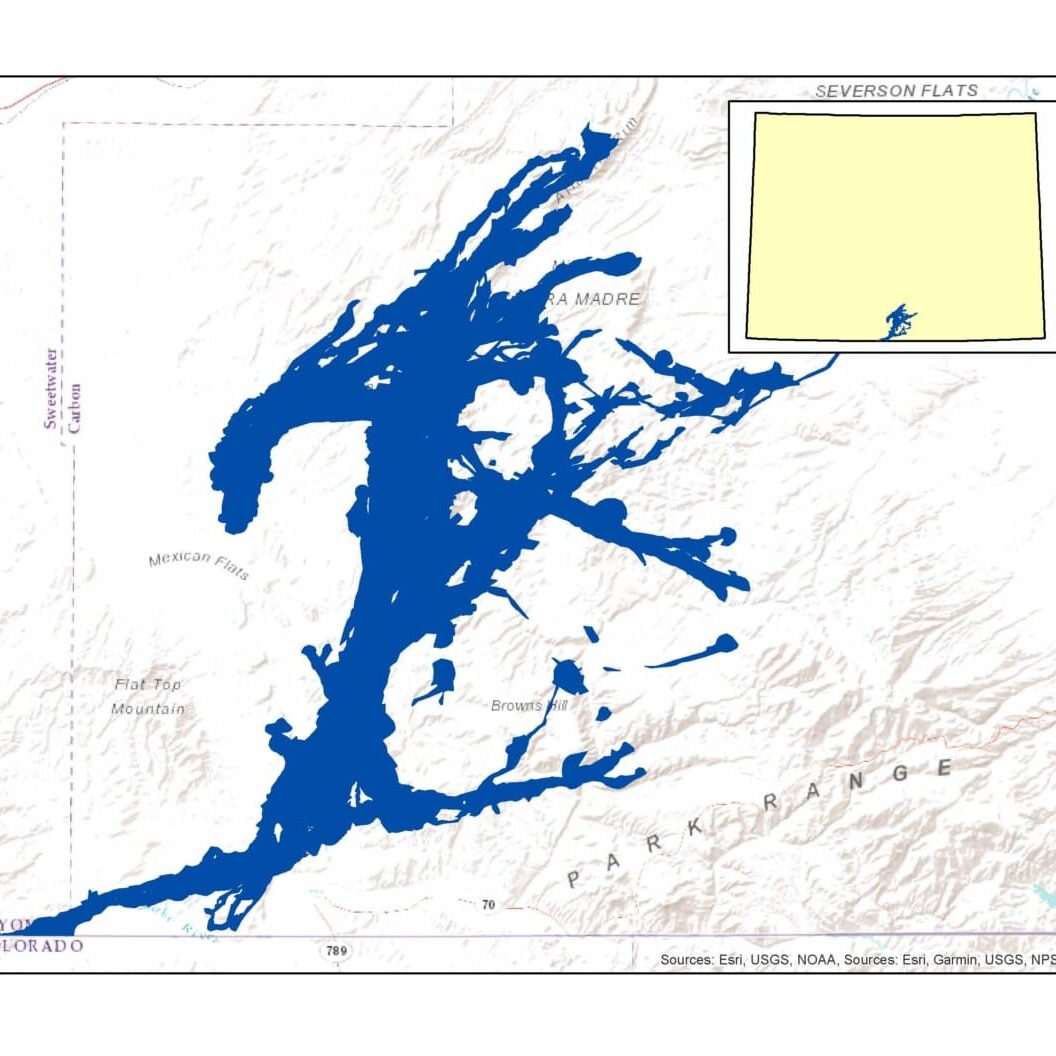

Current Migration Corridors of Interest

Latest Related News

Diverse voices for the Bridger-Teton National Forest

Public lands belong to all of us, and their future depends on diverse voices coming together. At WWF, we work to unite people from across Wyoming-recreationists, conservationists, local communities, and industry leaders-to protect wildlife and the landscapes we love. The Bridger-Teton National Forest …

Diverse voices for the Bridger-Teton National Forest Read More »

Volunteer For Mule Deer: Final Grizzly WHMA Volunteer Fence Day 2024

Volunteer For Mule Deer: FInal Grizzly WHMA Volunteer Fence Day RSVP & COMPLETE LIABILITY WAIVER HERE The Grizzly WHMA Volunteer Fence Day, set for June 15, 2024, marks a significant milestone in wildlife conservation efforts within the Baggs Mule Deer Migration Corridor. This …

Volunteer For Mule Deer: Final Grizzly WHMA Volunteer Fence Day 2024 Read More »

Hunters First Crack at Western Big Game: A Pronghorn Hunt Story

Southern Hunter’s First Crack at Western Big Game A First Pronghorn Hunt Story EDITOR’S NOTE: This hunt occurred in fall of 2022. Since then, this pronghorn herd saw impacts to their numbers from the harsh 2022-2023 winter and there are no pronghorn doe …

Hunters First Crack at Western Big Game: A Pronghorn Hunt Story Read More »

What We Do To Help

Wyoming Wildlife Federation has a number of specific Programs that address this

issue directly. Click on a Program in the list below to explore it in depth.