“The flesh of the cock of the Plains is dark and only tolerable in point of flavour. I do not think it as good as either the Pheasant or Grouse.” These words were spoken by Meriweather Lewis of the famous Lewis & Clark expedition duo, on March 2, 1806. Lewis doesn’t describe a very promising experience after eating, America’s largest grouse…the sage grouse.

Campfire Grumbles

I envision Lewis sitting around a campfire watching the old bomber spin slowly, over the orange flames. The bird had been cooking for some time. Droplets of the meat’s juices dripping off making a “psss” sound. A small band of men from the expedition party start gathering around. They come for the warmth of the burning fire on a cool evening and to watch one of their leaders eat the strange spiny-tailed bird. Lewis is still in awe at the size of the bird. A grouse no doubt, however, much larger than the ones they have encountered thus far. More than twice the size of those prairie fowl (Greater Prairie Chickens) encountered near the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in 1803.

The men watch quietly. They are hungry. The scene further expands as Lewis slowly rises after determining the bird is cooked and ready for consumption. He leans over, unsheathing his knife and slices off a chunk of the bird’s meat. Lewis looks at the dark piece of sage grouse and devours it, hoping to suppress his hunger after exploring all day. He chews and chews the tough poultry meat and finally swallows. Lewis’ face says it all to the men. The fowl did not taste good. Unbeknownst to Lewis the large gamebird had been overcooked. The men grumble. Grumblings are heard as the men walk away. Stomachs will be empty when the men hit their bedrolls for the night.

Lewis immediately questions the bird’s table fare to himself. Surely, such a fabulously adorned bird with its striking display of pointy tailfeathers and white millstone-styled collar ruff, would be edible…especially since the area’s indigenous tribes stalked the large grouse amongst the sage for food. The expedition had been sustained with various gamebirds since their journey had started. Most had been cooked similar to the likes of chickens. Lewis would give the order to not shoot any more sage cocks for camp meals and only to keep a few as specimens to send back for further study.

Questionable Tablefare

I’m fairly certain what I just described is a far stretch as to how the scene really unfolded. However, there is no denying the sage grouse often gets a bad rap for not being very palette-friendly. This makes it difficult to convince hunters and non-hunters that sage grouse is in fact edible and quite savory.

Truth be told, I was in the same boat back in 2019 when we traveled to Wyoming. It had been suggested that if we were going to eat sage grouse, we would need to shoot young birds. The reason…the young of the year birds are more tender, and the old bombers are heavy on the sage tasting scale and just did not eat well. My initial thought was how the heck were we going to judge a bird’s age while they were in flight trying to escape a string of lead pellets? It would be difficult for sure. Throw in a bird hunter’s excitement at the sight of a greyish blur flushing from the pale green sagebrush…and it makes deciding whether to pull the trigger difficult if you want a succulent tasting juvenile bird or a taxidermied old bird on your mantle.

Cooking With Sage

It was the end of the first day of the sage grouse season, and the opener had produced two birds. We had been forced to move from our primitive bird camp because our tent had sprung multiple leaks, to a huge, swanky ranch house on the property that may have been on the show, “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous”.

My best friend, Hutch, a rather talented food preparer, had found his Shangri-La in the residences’ five-star kitchen. He quickly put me to work, and I found myself tasked with cutting up potatoes and carrots while he tended to the grill. Cooking the birds so that they are somewhere in between rare to medium is essential for having a good experience eating sage grouse. With a pair of tongs, he repositioned the pieces of sizzling flesh, watching them closely so as not to overcook them. Hutch then grabbed a clump of sage he had brought from the very land we had hunted these birds from. With gentle strokes, he used the aromatic sage – nature’s cologne, to lightly butter the pieces of sage grouse. Hutch wanted to integrate the sage into the preparation. Though the small bough of sage was small, its wavering minty smell was powerful as it permeated the area.

Sprinkles of salt, pepper, and a hint of garlic were sparingly applied. He wanted us to savor the natural flavor of the sage grouse, but at the same time not mask the very plant that provided the birds with food, habitat, and life. Hutch’s goal was to bring out the meatiness flavor hidden within the bird. Moments later, Hutch walked in with a mustard-colored plate – on it, pieces of what appeared to be steak.

The meat was enveloped with slices of carrots, and chunks of red potatoes. A light-colored brown stock of juices laid the foundation for the dish. After blessings were given out to our kindred fellowship, forks found themselves impaling vegetable and cubes of fowl. The piece I bit into was mouthwatering. A slight taste of sage was detected but it brought out and intensified the flavor. If I hadn’t shot one of the birds, I would swear I was eating a lightly cooked steak. There was not a gaminess associated to the bird. Going from hunting the wide and expansive sagebrush, to watching such massive gamebirds take flight, to culminating the experience with eating the birds we had traveled such a long distance for was rewarding. I think it was appropriate that there were remnants of sage with our meal, as it completed the circle of the hunt. The sage connected us to the land and to the bird.

Tailgate Poultry

A year later I found myself once again in Wyoming for the sage grouse opener. This time, our party of five had some help with a duo of new acquaintances who crashed our bird camp. Rick was retired and once again participating in Wyoming’s sage grouse season as he had done for many years. Trey, a college student was traveling with his dog chasin’ birds throughout the west and southwest. The two themselves had only met just prior to our arrival. Our group meshed quickly and soon it felt like we had known each other for years. They provided great local knowledge, which led to limits of sage grouse.

At the end of our first day together, we had a bounty of birds. They ranged in age and size. The smaller grouse were obvious young-of-the-year birds. Their coloration and lack of such a multi-pointed tail were evident of their youth. I found it amazing, shooting 7 ½ shot brought down the various sizes of sage birds quite easily. We are talking stone cold dead in the air. This was evident in the display of birds I had neatly laid out in the dirt upon our return to camp. The birds ranged in dimensions: S, M, L, XL, and XXL for the huge bomber that Sam Wells had shot earlier in the evening. There would be plenty of meat to eat for dinner.

We were all tired from walking the expansive and delicate sagebrush and ready to nourish our tired bodies. Prep time would have to be simple, yet quick to fill empty bellies. We had opted to do the cooking and share a meal at Rick’s campsite instead of ours. Rick offered up a package of bacon, and we threw in an onion and hand-made tortillas that I had brought. Easton, Dan’s fifteen-year-old son, rummaged through their field pantry and presented a mixture of seasoning. We made do with what we had in the truck.

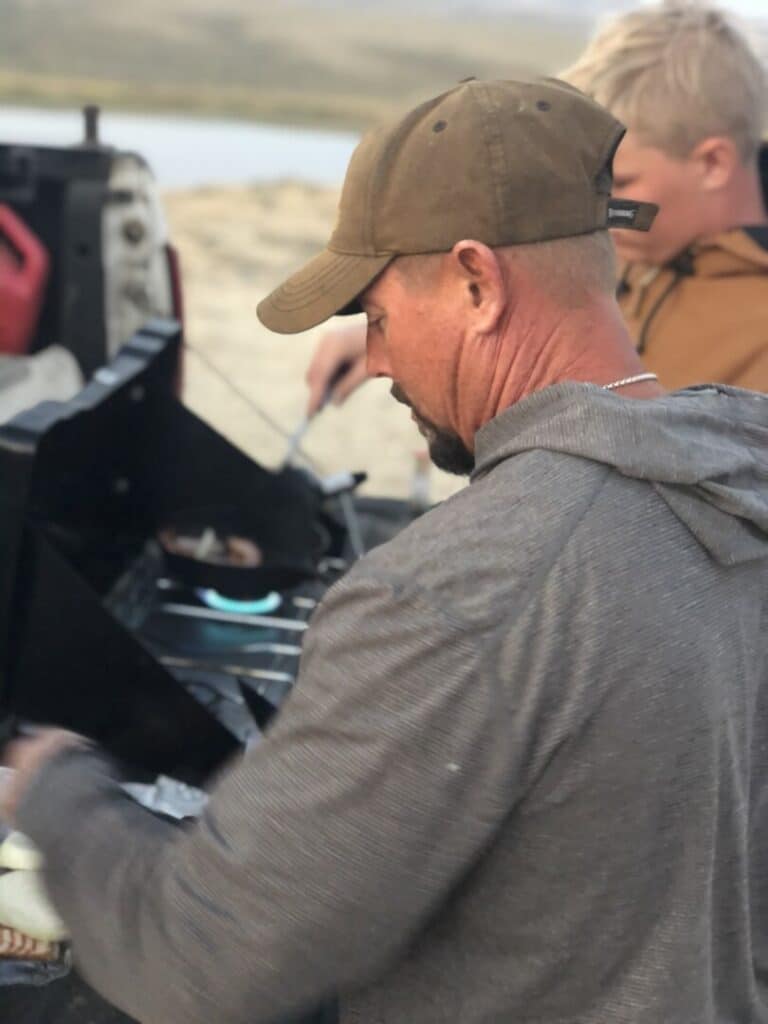

Damin, the driving master of traversing the Wyoming landscape in his Ford F350, joined up with Easton and the two quickly set up a field kitchen on the tailgate of his truck. He took it upon himself to head up chow as I cleaned birds. Two sets of stoves, one for the birds (that’s funny) and one for heating up the tortillas, were fired up. The low hissing sound from the propane, was soon drowned out by campfire tales as Rick, Dan, and Sam encircled themselves in lawn chairs. The day’s events retold with hand gestures, excited voices, and references to bird dogs who lay beside each owner. It was evident that the dogs were tired, as they had fallen asleep. Dreaming of sage grouse, no doubt.

I walked over to watch our two camp chefs. Damin, was gently placing the flimsy white tortillas onto the grill and Easton was sprinkling just a hint of the seasoning onto the sage grouse. With a fork, Damin set to work making sure the birds weren’t over cooked. He was going for a light searing on both sides. The bacon grease and onions would add flavor and make for crunchy bites. The onions were beginning to caramelize, and the crackling noise made for a subtle break in the silence. Herds of pronghorn could be seen across the lake coming to water for the evening after grazing all day.

The sun was slowly disappearing. Daylight was lingering on. The sky was morphing from a bright blue hue to shades of orange. Soon, dinner is announced. Rick is given the honors to try this haphazard put-together meal. Damin hands Rick a paper plate with a tortilla, adorned with slices of grouse breast, a few strings of onions, and a slice of bacon. It is not a pretty dish, but we don’t care because we’re all hungry.

Rick doesn’t wait, to sit down and rolls the flour tortilla up. Several seconds pass and he manages to swallow the mouthful of ingredients. He declares the “grouse wraps” delicious. The rest of the evening is spent talking about birds and the next day’s agenda – only to be periodically interrupted for a second and third helping of grouse.

Redemption

I’m fairly sure most wingshooters will agree that among all the upland game birds, the sage grouse has the worst reputation when it comes to passing the taste test. There seems to be a natural hierarchy within the upland bird community as far as being culinarily appetizing.

No matter which quail you hunt and eat, they ALL are delicious! And we all know about the immigrant Chinese bird that plays havoc to bird hunters and dogs alike, he’s rather quite tasty too. Though personally I have not hunted nor eaten ruffed grouse, I don’t want to risk a complete uprising, and omit what those up in the Northwoods will probably say is the best tasting bird out there…The King. Even the medium to rare cooked timberdoodle, whose taste is akin to being described as earthiness, is a good meal. Let’s not forget America’s flying appetizer, the dove, it is a crowd favorite wrapped in bacon throughout September. Anyone of these gamebirds could easily take top honors in the kitchen or around the campfire.

But alas, the ever-so delicate sage grouse, who seems to be encircled with a host of habitat, conservation, and hunting issues is once again on the chopping block…but this time as a bird not so favorable to our tastebuds. Many times, it comes down to simply how a gamebird is prepared and cooked. It doesn’t help that a journal entry hundreds of years ago by Lewis help fuel the notion that sage grouse are just not particularly good to eat.

It seems the bird’s “sagey” taste has followed it throughout history. A recent find in a 1963 book shows that even with the advancement in the culinary arts well into the 1900s, people were still being warned about the taste of sage grouse. “…shoot the smaller, younger birds because the adult birds were so tough and tasted strongly of sage…”, pretty much tells readers to bypass old bombers. The section on sage grouse goes onto say “The modern pressure-cooker helps greatly in unbending the noble old cocks into something fairly palatable.” At least the author threw in some encouragement! Heck, even famed writer Ernest Hemingway preferred to eat “young sage hens”, when it came to gamebirds.

As I stated in the beginning of this article, our group was told to stay away from shooting sage grouse altogether, as their sagey flavor and tough meat was not appetizing. We ignored such notions and suggestions and went with our gut. As it turned out, both times we have hunted Wyoming, we culminated each evening upon our return to bird camp with a feast of lightly cooked sage grouse prepared in a variety of ways. From elaborate dishes with all the vegetable fixings to simple campfire meals made with what was on hand. To hunt the sage grouse, and then to eat the bird is to honor such an iconic symbol of the wild and delicate sagebrush.

I end with tossing aside the sage grouse’s poor reputation as edible and embrace the hint of sage in every morsel. Consume the bird you have traveled so far to hunt, and you too will be connected to the sage landscape.

About the Author

Follow the author’s adventures on Instagram @hunt_birdz