107 years ago, a well-known American zoologist, conservationist, taxidermist, and author lobbied national leaders to help the sage grouse.

On June 6, 1805, near the Marias River in Montana, the world was introduced to a “Fowl of the Pheasant Kind” as large as a turkey. Its coloration a mixture of dark mottled brown, with small black specks with a long, spiny pointed tail with legs feathered to the base of the toes and fleshy yellow combs over the eyes. It emits a swishing sound along with a series of cooing notes, followed up with what can be described as popping sounds similar, to the uncorking of a champagne bottle. Such a bellowing sound surely caught the attention of explorers.

The ground-dwelling bird flourishes amidst the sage landscape and feeds on sagebrush. The large bird was seen by Lewis and Clark during their expedition after an unsuccessful attempt was made to kill one. It was not until October 17th of that year that several were shot. Clark called it the “prairie cock”, while Lewis referred to it as “cock of the plains”. We know it as the Greater Sage Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus).

Untold Numbers

However, this spectacular bird no longer flourishes in the millions as it once did during the 1800s alongside the buffalo. Nineteenth-century travelers reported seeing huge flocks of sage grouse that “darkened” the sky as they lifted from the valley floors. George Bird Grinnell, known as “The Father of American Conservation”, wrote in October 1886, he witnessed “great numbers” of sage grouse fly over his camp just south of present-day Casper, WY. Looking up from camp at the edge of a nearby bluff, hundreds of birds were observed as they took flight. Those birds were replaced by others who stepped forward. Grinnell said the number of sage grouse that took flight reminded him of the old-time flights of the extinct passenger pigeon.

Traveling settlers hunted the plentiful bird for food and collected sage grouse eggs in the spring. There are reports of pioneer hunters killing a hundred in one day without the aid of dogs! The late 1800s and early 1900s brought about heavy exploitation of sage grouse by commercial and sport hunting.

Sage grouse now number in the thousands (140,000-250,000), a mere ten percent of their historic numbers. But, even during their peak, there were those at the time that cautioned their demise and started to fight on behalf of the sage grouse. Even going as far as to writing to the president for help as sage grouse populations started to diminish.

Over the past century, the sage grouse population has plummeted as almost half of the sagebrush habitat has been lost. Since the time of Columbus, the sage grouse range, which encompassed sixteen states from as far as eastern Oregon to the Dakotas and Nebraska, then southward to New Mexico and Arizona, and east to Oklahoma, has diminished to only a handful of states. Wyoming leads all other states as being the stronghold for greater sage grouse and having the most leks within their range. It also is home to 43 million acres of sagebrush, more than any other state.

Predicting The Sage Grouse’s Plight

1999 brought about the first petition from conservation groups requesting the protection of the sage grouse and the plight of the delicate sage ecosystem. However, the call for protecting the sage grouse goes farther back to more than a hundred years. William T. Hornady (1854-1937), an American zoologist (1st director of the Bronx Zoo), conservationist, taxidermist (chief taxidermist – U.S. National Museum), and author, wrote a paper in which he predicted the sage grouse would be the first of the upland game birds to become extinct.

In 1913 Hornady wrote, “Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation”, whereas he was certain the sage grouse would become extinct among with two other species of grouse (prairie chicken and sharp-tail grouse). Hornaday was adamant that unless conditions surrounding sage grouse were immediately changed, the bird would be difficult to save and share the same fate as the heath hen.

He explained the sage grouse only exist in small “shreds and patches” from their original ranges. He decried hunting was not the only issue but also loss of habitat and range. Hornaday had the fortitude to see into the future and helped lay the groundwork to where we are today in our struggle to save the sage grouse and their habitat.

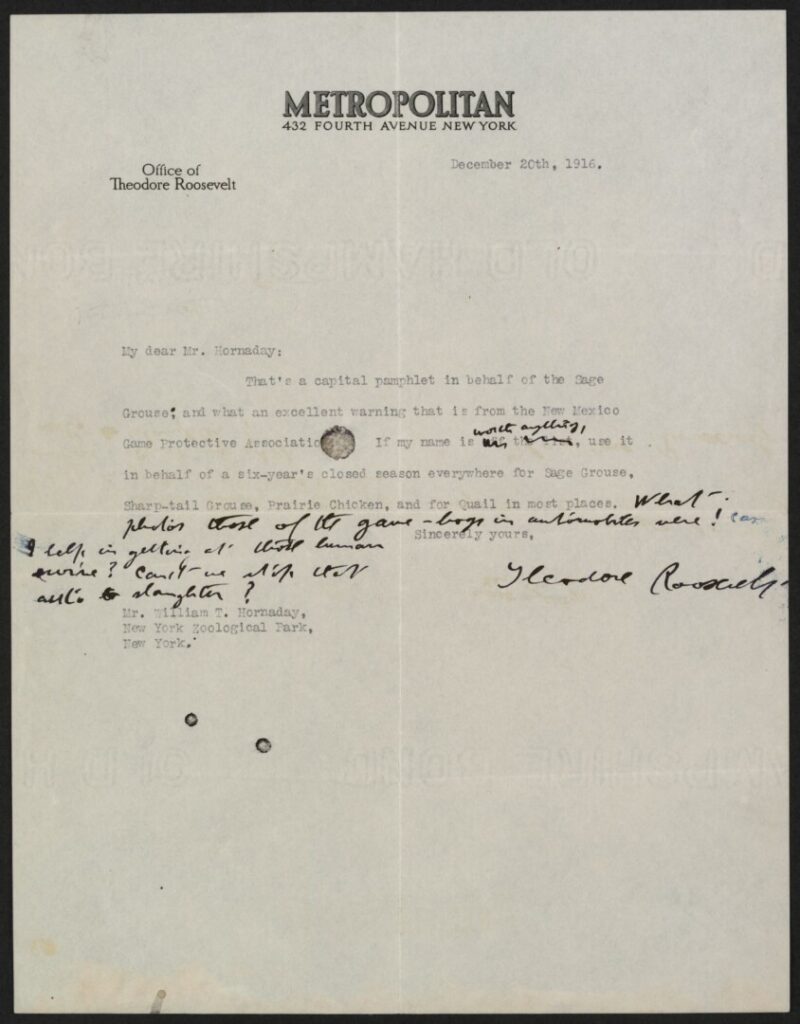

Hornaday followed up with a pamphlet in 1916 titled “Save the Sage Grouse from Extinction: A Demand from Civilization to the Western States.” Hornaday’s lobbying efforts included countless press releases and letters to state and national leaders, one of those is former President Theodore Roosevelt (1859-1919).

Roosevelt

In December of that year, Roosevelt writes to Hornaday complimenting his pamphlet on sage grouse. He tells Hornaday to use his name if it helps close the season on sage grouse, prairie chicken, and quail for six years.

Three months later in March, Roosevelt writes to Hornaday to inform him that he has wired “Stephens” (Dr, T.C. Stephens, was a well-known Iowa conservationist) approving the closed season on quail and prairie chickens. There is no specific mention to sage grouse. Why did Roosevelt take such an interest in Hornaday’s fight to save the sage grouse? Many do not know that Roosevelt was an ardent birder, both from a scientific and hunting aspect. His first writings were on birds.

Roosevelt’s hunting adventures for big game are well-known and documented, however many do not know he holds a much deeper connection with sage grouse than commonly known. My first introduction to Roosevelt’s claim to being, a bird hunter is a water-colored painting by Henry F. Farny (1847-1916), titled Theodore Roosevelt “Sage Grouse Shooting”. It depicts Roosevelt walking amongst the sage brush carrying a shotgun while a Native American helper carries a sage grouse.

Roosevelt’s interaction with sage grouse goes back to when he chronicles his western exploits when the 27-year old publishes Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, in 1885. In Chapter III: The Grouse of the Northern Cattle Plains, Roosevelt writes about riding out on his horse with shotgun in hand stalking “sage fowl”. Roosevelt describes the sage grouse as handsome and is very characteristic of the regions which the bird inhabits. I would be wrong to incline that Roosevelt somehow knew the almost symbiotic relationship sage grouse had with the land, and its source for its continued survival and existence.

It is my belief that Roosevelt’s interaction while hunting sage grouse planted a deep-rooted understanding in which why he responds to Hornaday’s pamphlet. He was as serious about hunting as he was about conservation.

Hunting Seasons Close Due to Dwindling Population

By the 1920s, sage grouse numbers start to decline, with it the sage brush. This trend continues into the 1930s which causes many states to close hunting seasons. The 1931 Wyoming hunting season calls for two days (08/16-18), with a daily limit of six sage grouse. The public is alerted to the impacts of human expansion into the sagebrush-steppe. With hunting seasons closed for several years, the 1950s see an increase in sage grouse numbers thus opening limited hunting season with reduced bag limits. Populations start dwindling again in the 1960s and 1970s.

History Sends A Message

Hornaday was able to predict the struggle the sage grouse would endure in the coming years. The sage grouse battle surges on many fronts…over development, grazing, degraded and fragmented habitat, mining, and several other issues. If history teaches us anything, we need to look to the past to see that if nothing is done or if our response is too late, then we could lose such an iconic bird and its fragile habitation.

For centuries we have admired the sage grouse and its precious sagebrush sea. Both have become ambassadors to the once vast sage prairie that sprawled across to more than a dozen states. The time is now to respond and act. As hunters and outdoorsmen, we owe it to those that fought for protecting such a vital resource for us to enjoy.

Author Edgar Castillo is a twenty-five plus year veteran law enforcement officer for a large Kansas City metropolitan agency. Edgar also served in the United States Marine Corps for twelve years.

He longs for the colors of autumn and for frosty, winter days so he can walk the landscapes in pursuit of wild birds in wild places. Besides his faith and family, his passion lies in the uplands as he self-documents his travels across public lands throughout Kansas hunting open fields, walking treelines, & bustin’ through plum thickets.

Find him on Instagram @Hunt_birdz

Citations:

- President Theodore Roosevelt mounted for a gallop near Laramie, Wyoming – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. - Our Vanishing Wild Life, by William T. Hornaday (Image courtesy of Project Gutenberg) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13249/13249-h/13249-h.html

- Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to William Temple Hornaday. Theodore Roosevelt Collection. MS Am 1454 (15-3). Harvard College Library. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o283394. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.