The history of wildlife science and conservation in North America is chock full of great men. From John James Audobon to Gifford Pinchot to Aldo Leopold, we could fill pages with their names. Less well known are the women who contributed significantly to the history of wildlife biology and conservation. Here are just a few of those trailblazers:

Enid Michael (1883-1966)

Enid Michael’s life was typical of the times she lived in until she was in her 30’s. She taught public school in Pasadena but was an active member of the Sierra Club and avid rock climber. On one of the club’s field trips into Yosemite, she met and fell in love with the postmaster, and moved to the valley. An avid outdoorswoman, Enid convinced the park superintendent to hire her as the first-ever ranger-naturalist in Yosemite and the first female ranger in the National Parks system. She served in that capacity for over twenty years, retiring in 1942. Over the course of her life, she was a prolific writer, publishing over 500 papers on the flora and fauna of Yosemite National Park. These papers are the largest body of work of any single writer on the natural landscape of Yosemite.

Frances Hamerstrom (1907-1998)

Born into wealth and privilege, Frances (Fran) scandalized her family by being a tomboy who went everywhere with her gun and practiced her taxidermy skills on her take. Thoroughly bored with her undergraduate work in Iowa, she applied for and became the only female graduate student to study under Aldo Leopold along with her husband-to-be Fred Hamerstrom. While Fran never minced words and never backed down from a challenge, no one would hire a female wildlife biologist, so Fred would get a paying job and Fran would do the work of a biologist while only getting credit as a volunteer. Fran studied birds across the US, but her most significant contribution is an understanding of the mating behavior of the prairie chicken. Knowing the unique habitats prairie chickens required for their leks led to the conservation of these habitats and is one of the primary reasons these birds are still found in the upper midwest today. Fran also wrote 12 books and 150 scientific papers over her lifetime.

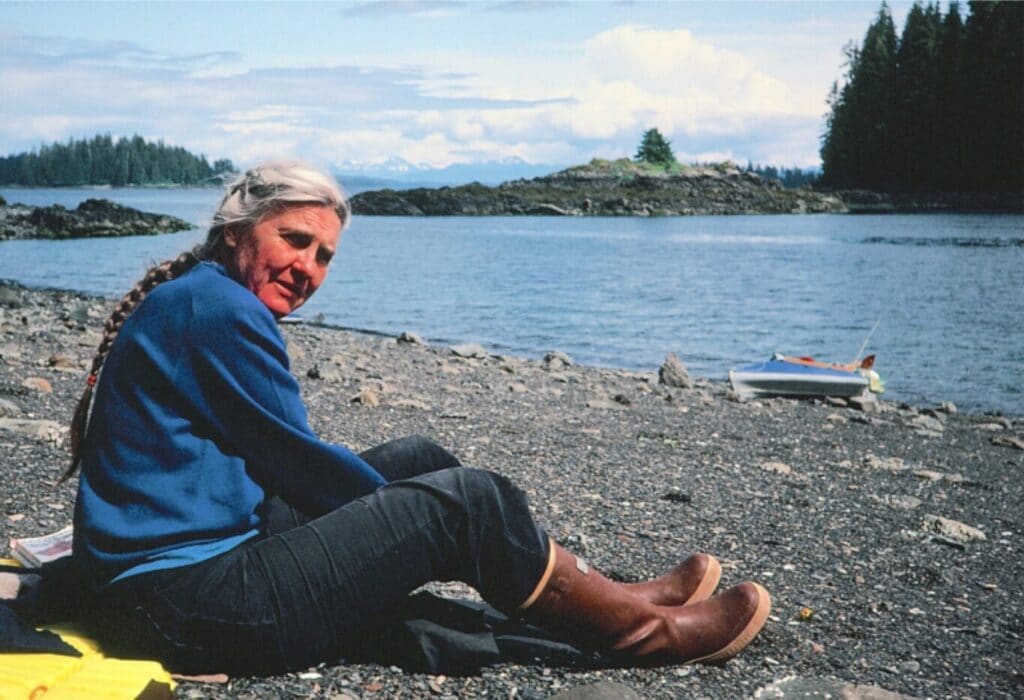

Celia Hunter (1919-2001)

Celia Hunter was born at the foot of the Cascade mountains in Washington and grew up working her family’s farm during the Great Depression. As World War II approached, Celia wasn’t content to sit back. She joined the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) and learned to fly cutting-edge planes. Ferrying planes wasn’t enough for Celia, though, she wanted the challenge of flying over terrain considered too dangerous for women at the time, Alaska. So, Celia went private. Along with her husband, she began a successful outfitting business in Alaska, Camp Denali. Celia fell in love with the unspoiled wilderness of Alaska and this sparked a second passion for conservation. Along the way, Celia became the first female president of the Wilderness Society and successfully lobbied to protect over 100 million acres of Alaskan wilderness. At 82, Hunter spent her last day on Earth cross country skiing near her home in Fairbanks and writing letters to congress supporting Alaskan conservation.

These gutsy women and so many more have paved the way for today’s wildlife biologists. While there are still hiring and wage gaps for women in wildlife, these pioneers have led to a world where women make up more than half of wildlife graduate students and more than half of the employees of Wyoming Wildlife Federation.